[This epic tale about a tightfisted man refusing to use the correct Chinese names for most of his life is from the brand-new CHINA HANDS HANDBOOK. You are crazy not to get YOUR HANDS on the epic China Hands Handbook, HERE!]

Yorick L Mackenzie was a Scottish explorer who had travelled to every corner of the world in search of hidden places and exotic beasts. But his latest quest was his most challenging yet, as he chased the enigmatic ‘Tao monster’ through a labyrinthine collection of Western fiction.

The Scotsman had first heard of the Tao monster from a monk during his journey into Tibet. The monk had told him that the creature had to be an incarnation of the Tao, the ancient Chinese philosophy that harmonizes order and chaos. “You foreigners, very afraid of monsters, no?”

When Yorick ascended to the monastery, a group of monks warned him that the Tao monster had already seduced the great authors of our time, and that all science and fiction in the world were in fact a manifestation of the Tao. “But wait, aren’t you Buddhists?” the explorer said. "We are Buddhists, and we are Chinese also. We are Chinese Taoists also," the monks replied.

Undaunted by this warning, Yorick continued his journey eastward to Shandong, the birthplace of Confucius. There, he visited a temple where a group of learned men told him that Confucius had not seen the monster, but that he indeed believed the world was an embodiment of the Tao. “But wait, aren’t you Confucianists?” the explorer said. "We are Confucianists, and we are Chinese also. We are Chinese Taoists also," the learned men replied.

Confused by what Chinese riddles he had encountered, Yorick returned to Scotland, determined to chase the enigmatic monster through all the British libraries. It was true that many great authors had been obsessed with the invisible, supernatural Tao. Scholars such as Joseph Needham or Carl Gustav Jung. Writers like Alan Watts and Herman Hesse. Quantum physicists like Nils Bohr and David Bohm.

A cryptic librarian told Yorick that there existed a whole Tao industry in the West, but no Tao monster, with books like Benjamin Hoff's The Tao of Pooh and Fritjof Capra’s The Tao of Physics. The father of modern science, Albert Einstein himself, had been a disciple of Tao. “But wait, weren’t they Christians?” the explorer said. "They were Christians, and they were writers also. They were writing Taoists also," the librarian replied, before he disappeared with a puff.

Lost and confused, Yorick immersed himself in the storytelling of Herbert Wells, whose tales of time travel and alien invasion had captivated generations of readers. “The Tao monster had to be in horror, pulp, and space fiction also,” he thought.

As Yorick traversed through the strangest collections of fiction, he sensed a foreign allure emanating from these pages about the extraterrestrial and the otherworldly. It was as if the enigmatic being was reaching out to him, tempting him with its cosmic power of Qi. The Tao, as Yorick soon realized, was at once the most complex and also the most simple of all philosophies.

The Tao was at once a formless goo and the dream of a butterfly, and the profound blubber of a fish also. The Tao was at once resting in a drum tub and poking holes in wonton soup, and cutting up a cow like chef-cook Pow also.

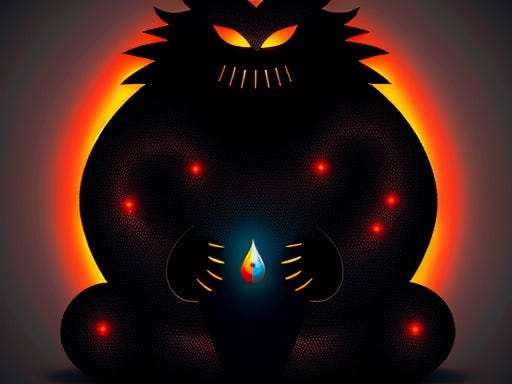

According to ancient canon, the Tao had been one, and one became two, and two became the many horrors. “The Tao monster expands but has no age. It can never be contained. It can never be killed,” Yorick thought. He shuddered.

Haunted by imaginations of the faceless foreign creature, Yorick ploughed through the works of Jules Verne and Isaac Asimov and Arthur Clarke. Each author's stories left him word crumbs that, he felt, would lead him closer to the Tao monster’s whereabouts. “These Western stories are all brim and gravid with Chinese Yin and Yang,” Yorick thought, “and the stories were Yin, and the writers were Yang, and Yin and Yang were borne of the primordial quality that was the Tao of the Universe.”

Science fiction, it burned in him, was only superficially a genre of Western entertainment. At its inception, it had to be a reflection of the basic human psyche, a manifestation of our fears of the timeless monster within us… and also, without us!

Eventually, after months of chasing the enigmatic Tao monsters in British libraries, Yorick found what he had been looking for. It was a dusty, old Chinese book hidden away in a forgotten corner of the university library, its chapters printed in medieval Chinese that he could barely decipher, but managed to just do so.

As he nervously thumbed through its caustic pages, he felt the mortal pangs of a shocking familiarity. There! There were warning notes, written by an unknown Scottish author: “Do not use foreign words!”

And here, on the final page of the book, Yorick saw it. The monster stripped of all its allegorical meaning, a shapeshifter between memory and premonition that threatened to take him into his creation, a final note of warning: “Do not learn Chinese!”

It was his own textbook, from his freshman year of studying Oriental studies in Scotland. He recalled how he had bought a copy but never bothered to rise to the challenge. How he had loathed the Chinese. How he had transferred to the English department instead. How he wanted to become a great writer. Exposed, overwhelmed, he plunged headfirst into this creation, ready to confront the enigmatic monster that so long had troubled him.

As he emerged on the other side of the world years later, Yorick found himself standing in a vast, open slope. The sky was a harmonious shades of green and blue, and the grass beneath his feet felt cool and awake. He was back again in Tibet where this story began.

And there, in the distance, Yorick saw a figure approaching. It was a Scottish adventurer looking for the enigmatic Tao monster. That foreign man now no longer seemed foreign to him.

“The four limbs of the monster,” Yorick explained to him, joyfully, “were but the four writer‘s virtues: Ren for Humanity, Yi for Righteousness, Li for Conduct, and Zhi for Wisdom.“ “But wait, aren’t you also Scottish?,” the explorer said. “I am Chinese, and Scottish also. I am a Scottish Taoist also,” Yorick replied, with total conviction.

Fear not the monsters from distant land’

Where ancient wisdom still command’

Embrace the teachings of the Tao,

The Chinese monster’s name was Yao.

End.

GET YOUR COPY OF THE CHINA HANDS HANDBOOK, HERE!

Good one! Wasn't James Legge Scottish?

Wasn't the creature from Gremlins a Yaogai? Chinese culture is full of critters and monsters, we just tend to trivialize the ancient civilizations.